–

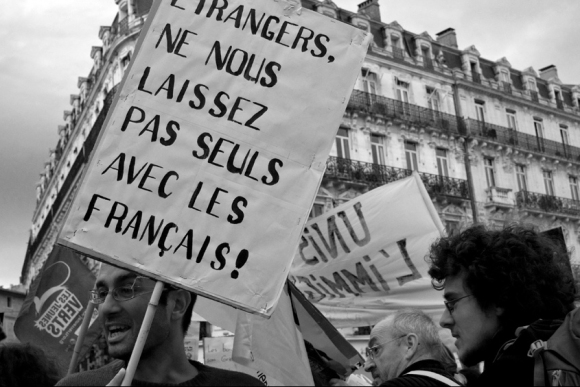

“Foreigners, don’t leave us alone with the French!” © 2010 Anne Petitfils

“Foreigners, don’t leave us alone with the French!” © 2010 Anne Petitfils

A strong opposition to immigration is one of the defining tenets of the Front National, the French far right,

a position which is met with much criticism from French socialists. Marine Le Pen, the party’s leader, sent shockwaves through the nation two weeks ago when she walked away with an unprecedented 17.9% of the national vote in the first round of this year’s presidential elections, although in the end it was

Nicolas Sarkozy (27.18%) and François Hollande (28.63%) who moved on to the second round.

–

une fête – a festival, a celebration, a party

un jour ferié – statutory holiday, civic holiday, public holiday, bank holiday

muguet – Lily of the Valley

faire le pont – literally “to make a bridge” (bridge a gap); an idiomatic expression used to describe the common French practice of taking a vacation day in between a statutory holiday and the weekend, thereby creating an extra-long weekend

le premier mai – the first of May

le syndicat – (trade) union

un ouvrier – a worker (historically, this term was used to refer to tradespeople or factory workers)

la classe ouvrière – the working class

une manifestation – a protest, a rally

le Palais d’Élysée – Élysée Palace, the official residence of the French president

Monsieur le Président – the proper way to address the French president, in the same way that English-speakers say “Mr. President”

le vrai travail – real work

la gauche – the left

un defilé – a parade, a march

le defilé syndical – the union parade

la crise – French shorthand for the current economic crisis or the recession

“travail, famille, patrie” – work, family, fatherland

l’extrême droite – the far right

le Front National – The National Front, the far-right political party in France. Their current leader is Marine Le Pen.

l’UMP – Union for a Popular Movement, the French political right. Nicolas Sarkozy, the current French president, is their leader.

le Parti Socialist – The Socialist Party, the French political left. François Hollande, current presidential contender, is their leader.

–

**********

–

“Do you hear the people sing, singing the song of angry men?

It is the music of a people who will not be slaves again.”

– “Les Misérables”, The Musical, Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg

–

This past Tuesday was May 1, otherwise known as La Fête du Travail (better known in English-speaking countries as “Labour Day” but literally translated as “The Festival of Work[ers]”). It’s hard to believe that it’s been two whole years since I first learned all about this nationwide jour ferié and its various traditions, like offering friends and family a small bouquet of muguet or taking an extra day off work to faire le pont. The last time I wrote about le premier mai, it seemed to me like just one of many random holidays that made the month of May in France seem like one long drawn-out vacation. What with it falling smack dab in between the two rounds of this year’s French presidential elections, however, the day took on a far more serious and political tone than many have seen in recent memory.

You see, in addition to being a great opportunity to take a long weekend trip somewhere, I’ve recently learned that, at its core, la Fête du Travail is meant to celebrate workers and workers’ rights. In Paris, the various big syndicats have a long-standing tradition of getting together to organize a big rally every year on this day, with the intention of uniting les ouvriers and reminding them of the importance of the holiday’s origins, of what their predecessors fought for, and of the fact that there are still battles that need to be fought today. It’s something of a sacred day to the unions, a day that has always traditionally belonged to la classe ouvrière. This year, as usual, the syndicats were on track to organize a giant manifestation at Denfert-Rochereau in the south of Paris, culminating in a grand march to La Bastille.

–

As a teenager, a high school field trip to watch the musical “Les Misérables” was my first introduction to French history, so it feels vaguely surreal to now be in Paris and witnessing strikes and marches happening along the very same city streets, carrying on the tradition of Victor Hugo’s famous unwashed poor.

As a teenager, a high school field trip to watch the musical “Les Misérables” was my first introduction to French history, so it feels vaguely surreal to now be in Paris and witnessing strikes and marches happening along the very same city streets, carrying on the tradition of Victor Hugo’s famous unwashed poor.

–

Then, President Nicolas Sarkozy, leader of the political right, made an announcement. Whilst up until now, he had been happy to remain at the Palais d’Elysée on May 1st, graciously accepting the basket of muguet traditionally offered to Monsieur le Président, this year, it was going to be different. This year, the nation’s leader announced, he was going to reappropriate the national holiday and return it to its rightful roots. And he was sending out an official call to arms, inviting his supporters to join him at Trocadero, at the foot of the Eiffel Tower (and, incidentally, on the doorstep of some of Paris’ wealthiest neighbourhoods), to celebrate “le vrai travail” (“real work”). The gauntlet had been thrown. The buck stopped here. Julio, you’d best be meeting him down by the schoolyard.

The declaration, particularly Sarkozy’s choice of the phrase, “le vrai travail“, created an instant uproar among union leaders and the political gauche, who considered it a deliberate dig at les syndicats, a direct attack on social programs, and a highly inappropriate attempt to exploit and politicize a holiday that had never officially been affiliated with any one particular party. Eventually, Sarkozy did backpedal a little on his original statement, first denying that he had used the phrase “vrai travail“, then conceding that it was an unfortunate choice of words. (“Ce n’est pas une expression heureuse.”) The acknowledgement, however, in no way deterred his determination to gather his supporters together in direct opposition to the défilé syndical. Some called it political grandstanding, a last-ditch effort to win votes and appeal to the far-right before the second round of voting takes place this Sunday. Others rushed to rally behind Sarkozy’s sentiments, tired of struggling through la crise and convinced that their hard-earned money was being used to support unrealistic social programs that are simply unsustainable.

If nothing else, Sarkozy’s decision to hold a massive public celebration in a deliberate bid to steal the syndicats’ thunder was a polarizing move in a city that already feels increasingly divided by class and circumstance.

To add to all the hullaballoo, Marine Le Pen and the Front National, in keeping with their usual tradition, held their own parade, gathering their troops by a statue of Joan of Arc and marching to Place de l’Opéra, in northwest Paris.*

(To get an idea of where the rallies were taking place in relation to one another, check out the illustrated map posted on France Info here.)

And so it was that on this past Tuesday, Paris did indeed hear its people sing, tricoloured flags raised high and proud, patriotic voices shouting out from all corners of the city. From my apartment window, I could hear the workers chanting in the distance as they marched to Place de la Bastille, determined to keep France the country of les droits de l’homme, firm in their conviction that the social mores and values which defined the nation after the French Revolution should still hold true today. To the west, Sarkozy and the UMP celebrated his redubbed “vraie fête du travail” (“the real festival of work'”), calling for a return to the French traditional values of “travail, famille, patrie“. And further north, in the shadow of the opulent Opéra Garnier, Marine Le Pen rallied the extrême droite, denouncing both the remaining left and right presidential candidates, and preaching what some consider to be a discourse of hate and fear, in the name of protecting France and its “rightful” French citizens.

Three different rallies. Three different sets of voices. Three very different visions of France.

What, I can’t help but wonder, would Victor Hugo say?

–

* Left presidential candidate and Parti Socialiste leader, François Hollande, said he refused to detract from “the workers’ day”, opting instead to go out of town to pay tribute to late socialist Prime Minister, Pierre Bérégovoy.

Leave a comment